William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen

Item

-

Title

-

William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen

-

Description

-

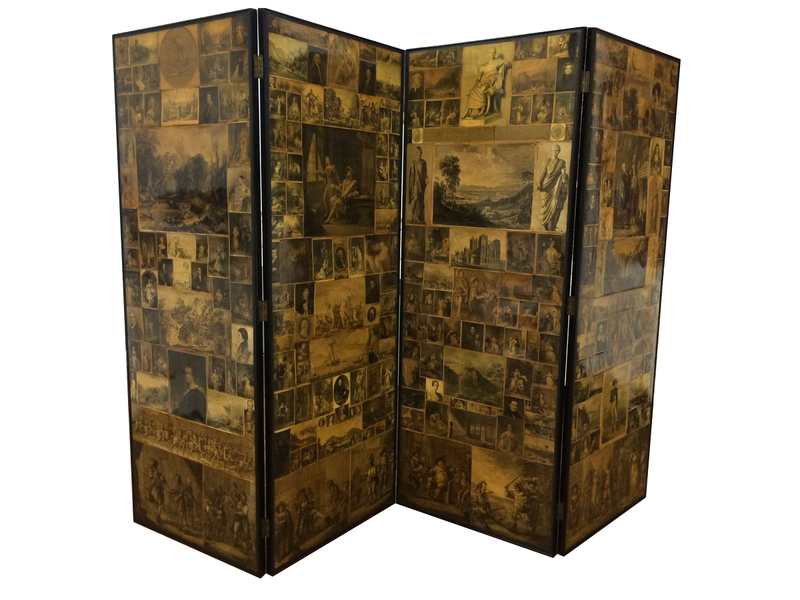

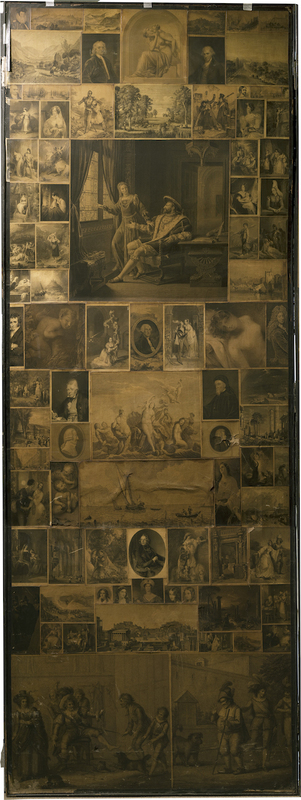

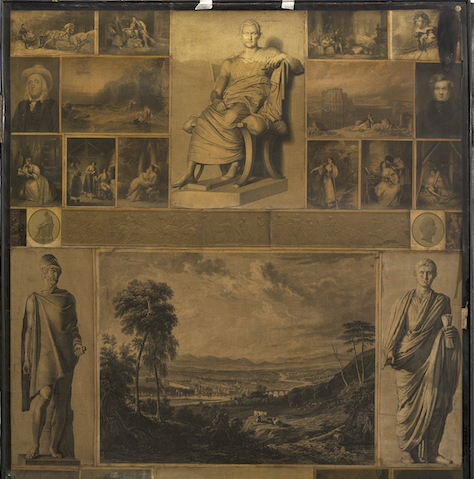

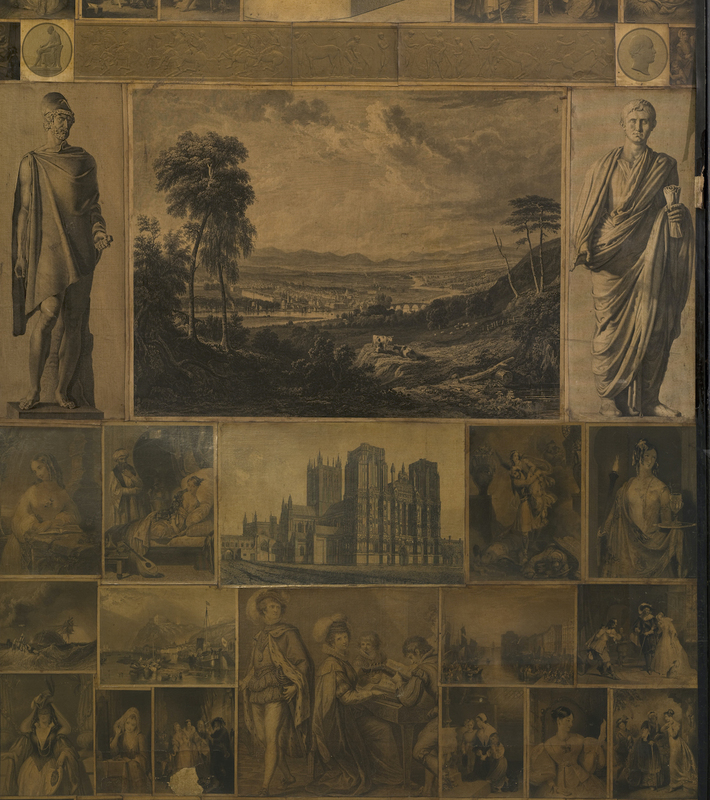

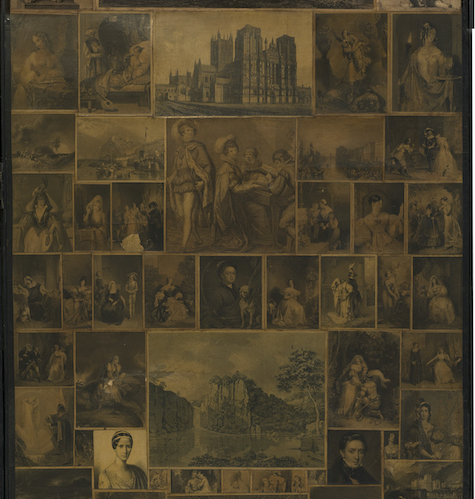

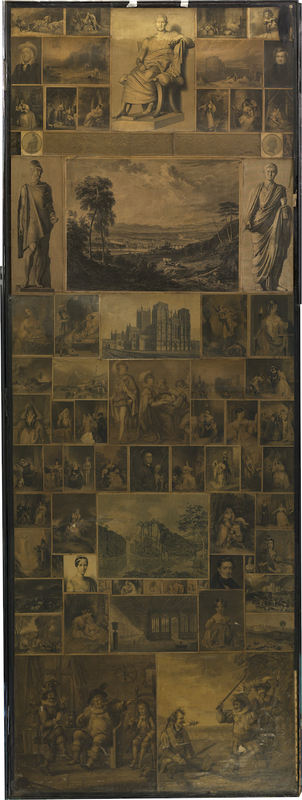

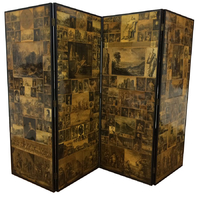

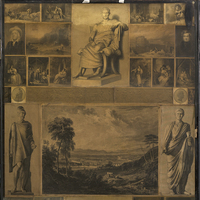

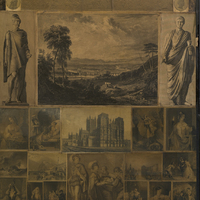

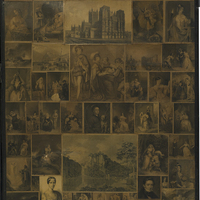

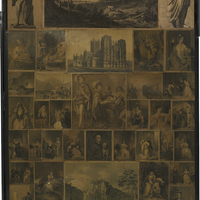

This elaborate folding screen is composed of four wooden leaves, each covered entirely by an assortment of square and rectangular paper cut-outs. Each individual leaf spans 202cm by 77.5cm, and the total length of the screen when extended is 310cm. Although the photographs above show only the front side of the screen, both sides are covered entirely in black-and-white images. Boasting approximately four hundred engravings overall, the folding screen displays an array of yellowed scraps of paper dating from the 1820s to the 1840s. These decoupaged images have been meticulously pasted onto the front and back of the screen and subsequently varnished. There are no gaps showing between the images, nor do their edges overlap. Covering a range of artistic genres, these engravings include portraits, historical paintings, and scenes from well-known plays. While the folding screen was made some time around 1860, the photograph above shows the object in its current state, housed in the collections of Sherborne House, in Dorset.

-

FREYA GOWRLEY ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

Dr. Gowrley tells us that this folding screen is attributed to William Macready and his friend Charles Dickens. The screen is currently in the collections of Sherborne House, where Dickens frequently visited Macready, a renowned Shakespearean actor in the Victorian period. According to family lore, the two worked together to produce this remarkable object.

The screen’s engravings are not arranged according to any self-evident system; however, the square and rectangular panels are arranged in a relatively orderly fashion, especially when compared to other surviving scrap screens from the period. Dr. Gowrley notes that the subjects include images of actors and actresses, scenes from Shakespeare, prints after well-known paintings, and even a portrait of Dickens himself.

According to Dr. Gowrley, the production of collage screens reached its height during the Victorian period, having emerged as a practice during the late eighteenth century. Made by decoupaging scraps and pieces of ephemeral paper goods on wooden screens, this form of material production exemplifies the broader impulse to assemble, collage, and create a single object from many smaller parts. In her project “Collage before Modernism,” Dr. Gowrley argues that this Victorian impulse disrupts the standard art-historical narrative positing that collage was invented by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in France in 1912.

Dr. Gowrley reminds us that existing art histories tend to figure collage as the result of modernist innovation rather than a medium with a long and distinctive history. Indeed, she affirms that when Macready and Dickens ornamented the surfaces of this screen with engravings in the 1860s, they were engaging in an aesthetic and intellectual tradition of collage production that had been prevalent for decades—one that would endure throughout the nineteenth century. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century collage represents a vital moment in collage history: thanks to the new availability of material and printed goods, an unprecedented variety of composite objects proliferated. Dr. Gowrley argues that scrap screens can be situated in relation to this proliferation in Britain and its empire, including the creation of traditional paper collage; bibliographic objects like scrapbooks and albums; and craft practices like paper cutting, quilting, and shell and feather work. Indeed, she reminds us that although the term collage is most often associated with paper, the centuries before twentieth-century Modernism saw a diversity of assembled forms.

For Dr. Gowrley, the distinction between “art” and “not art” prompts questions about how art is defined, the identities and motivations of those who made it, and why certain objects have been consistently overlooked by art history. She notes that this distinction reinforces entrenched hierarchies within art history, between high and low art forms, between modern and pre-modern art, and between artist and amateur—a hierarchy that, as Dr. Gowrley points out, is often gendered. She explains, however, that the Macready-Dickens screen complicates the simplistic narrative of art and non-art, of male artist and female amateur. Indeed, the screen is one of several made and owned by famous nineteenth-century men (many of them authors) from Lord Byron to Beau Brummell at one end of the century to Hans Christian Andersen at the other.

Though the screen is associated with Dickens, that most famous of nineteenth-century authors, Dr. Gowrley posits that only by placing the object within the context of Victorian material culture, and in relation to a longer art historical trajectory of collage, can we truly understand its disruptive potential as an object that complicates boundaries between elevated and lowbrow, masculine and feminine.