Mother's Petition to the Foundling Hospital

Item

-

Title

-

Mother's Petition to the Foundling Hospital

-

Description

-

This bundle of folded papers bound together by a white cloth ribbon records fascinating and moving stories: they are petitions completed by nineteenth-century women who applied to have their infants taken in by the London Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children’s charity Coram (http://www.coram.org.uk).

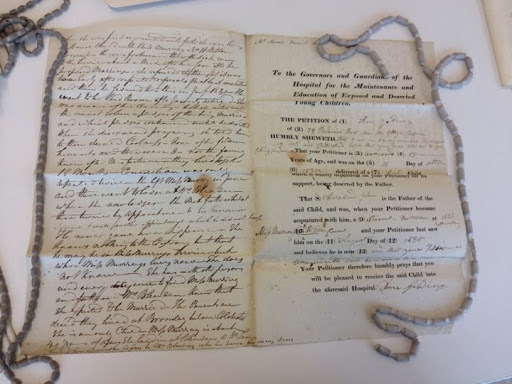

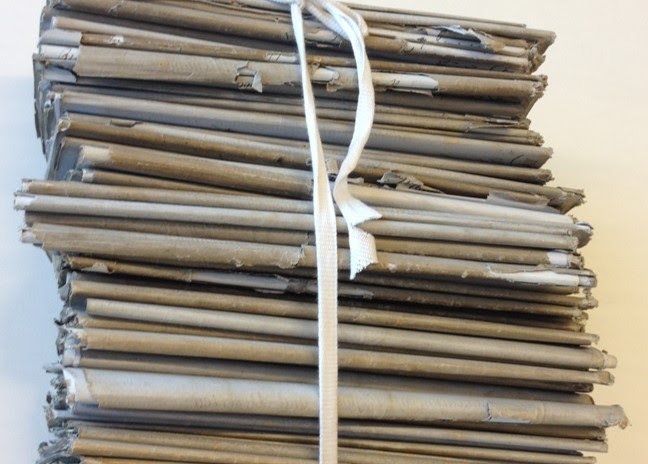

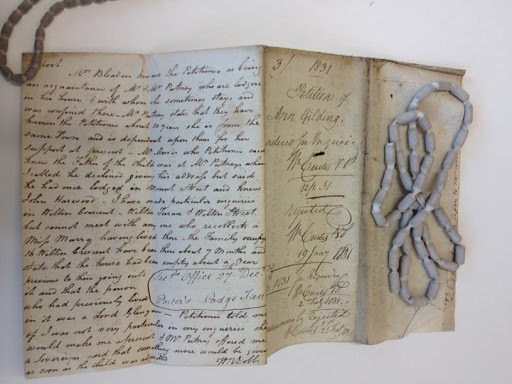

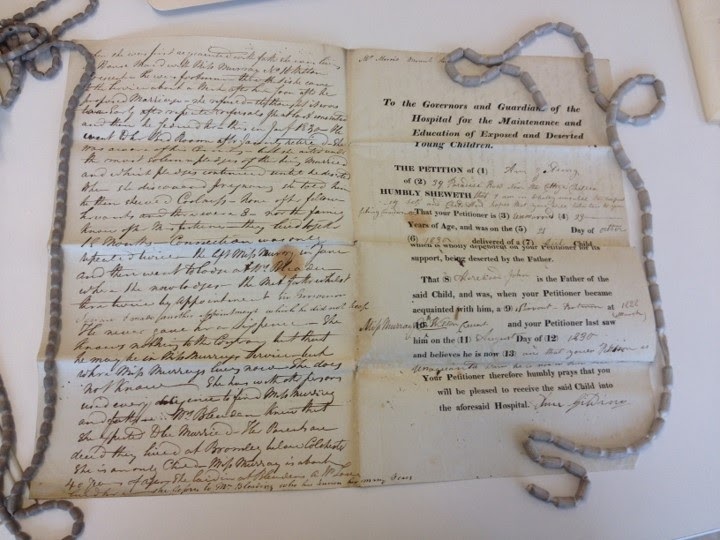

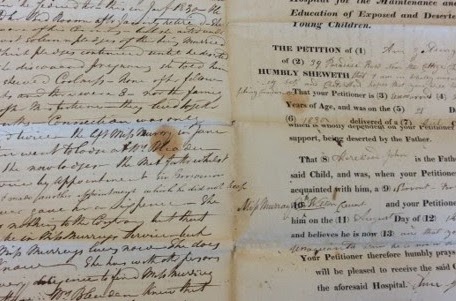

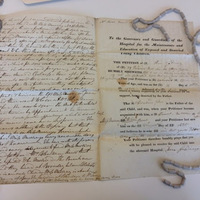

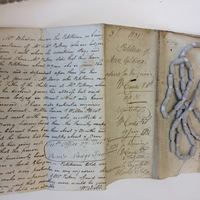

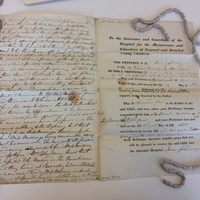

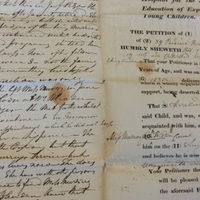

One photograph included here shows the bundle of folded petitions, each petition containing other documents (including letters and reports) relating to an individual application. Additional images of a single, unfolded, sheet of paper filled with typed and written text present the petition of Ann Gidding, a mother who applied to the hospital in 1831. One of these images shows the back of the petition, which documents the outcome of Ann’s application (in this case a rejection as a bribe had been offered), as well as the report from the Hospital Inquirer, who was employed to uncover the character of the applicant. Another image shows the form that all applicants were required to complete, as well as the transcript of Ann’s oral testimony given in front of the all-male governing body as part of the application process. Like the Inquirer’s report, this testimony is reproduced in a mass of cursive penmanship that narrowly escapes spilling off the bottom of the page. Uniform creases produced by the petition’s mode of storage and staining of unknown origin are visible in the images.

-

VICTORIA MILLS ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

Dr. Mills urges us to examine the materiality of mothers’ petitions to the Foundling Hospital and to consider the relationship between the material qualities of these paper objects and the moving and often disturbing testimony of mothers that they support. She emphasizes that the petition bundles are deeply collaborative objects, consisting of the spoken testimonies of women transcribed by the Hospital Secretary, supporting letters from women’s former employers and relatives, and other documents (for example, the reports of workhouses and lying-in hospitals), given in evidence as part of investigations into the character of a female applicant. Each petition represents a woman’s voice, albeit one that is, in Dr. Mills’s words, “mediated by a male transcriber.” While the stories contained in the petitions give us an insight into the lived experience of mothers applying to the Hospital, Dr. Mills cautions that through archival research, we may be compromising women’s attempts to restart their lives “without the taint of fallenness.” She adds that in focusing on a single petition, like Ann Gidding’s, we mirror the Hospital’s original selection process by choosing whose story to tell and thus value.

Dr. Mills highlights that the bundles are continually reshuffled as researchers interact with the archive, and that this reshapes our understanding of women’s experiences. Dr. Mills draws our attention to three practices of folding: the folding of the petitions as part of the apparatus of bureaucracy; enfolding, which acts as a form of protective embrace for these women and their stories; and the act of unfolding undertaken by the researcher—a practice involving forms of tactile intimacy with paper that is itself revelatory of intimacy. In unfolding the files, Dr. Mills ponders whether, as researchers, we engage in a continued violation of the women as we read the accounts of (often violent) sexual encounters. Do we take pleasure in what we read? If so, Dr. Mills asks, what is the relationship between our embodied engagements with these paper objects, the historical evidence they support and the ethics of the archive?