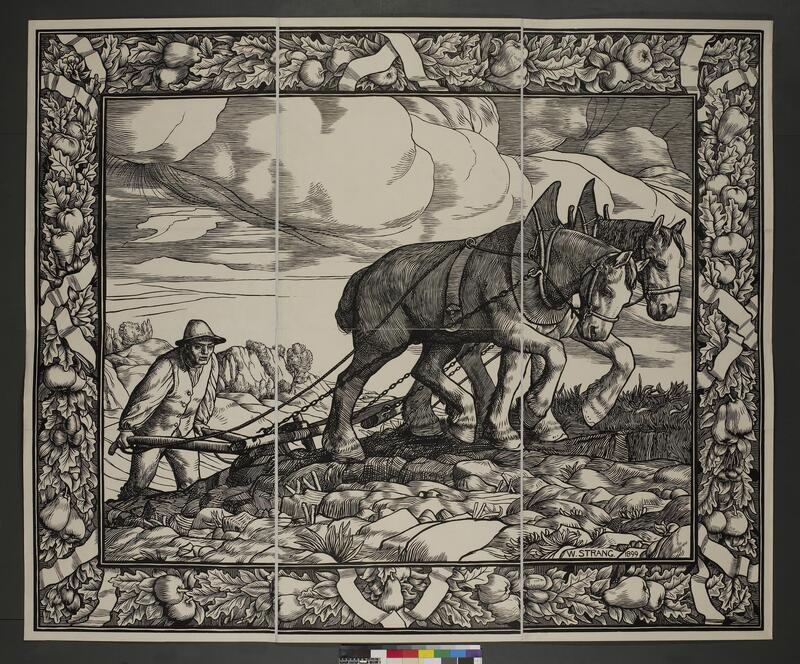

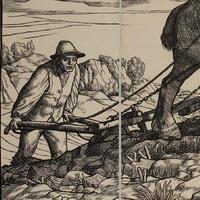

William Strang's "The Plough"

Item

-

Title

-

William Strang's "The Plough"

-

Description

-

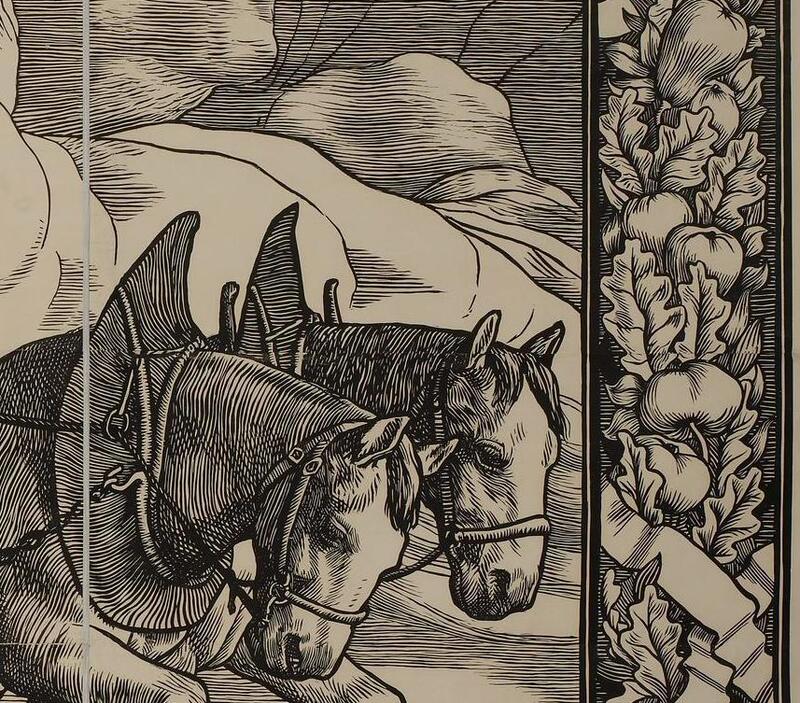

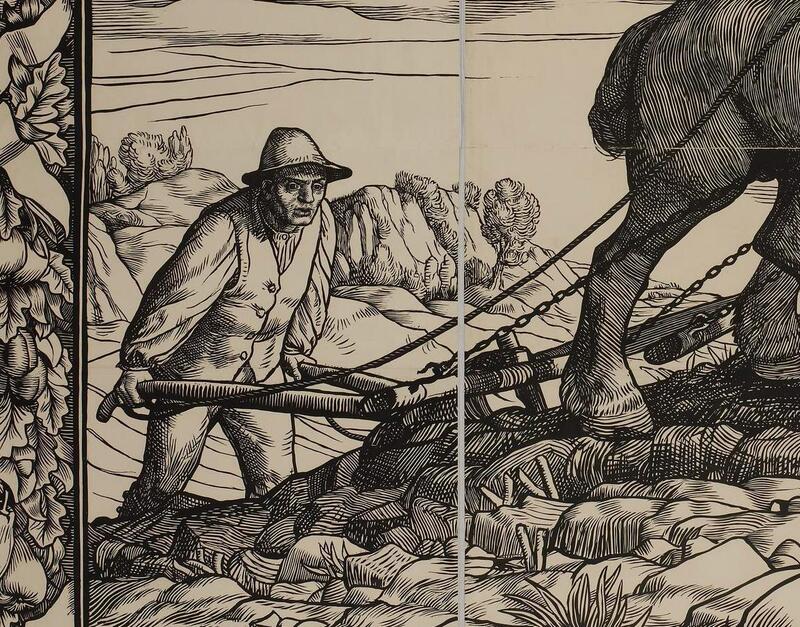

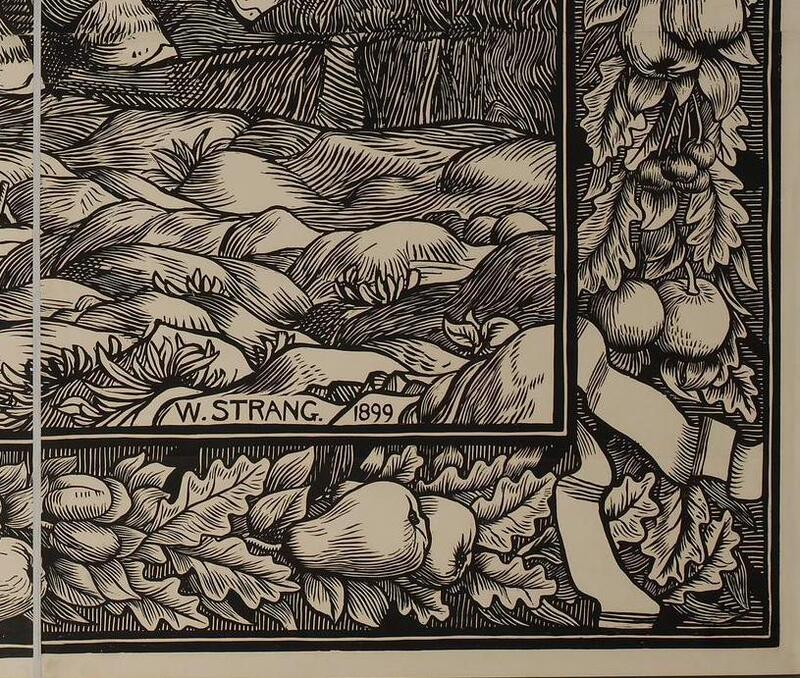

“The Plough” is an extremely large woodcut print, measuring five feet tall by six feet wide and printed from nine separate wood blocks. Created by artist William Strang for schoolrooms, the image is made up of individual black lines forming patterns of light and dark. The central image focuses on two large horses harnessed to a wooden plough that loosens and turns the soil while a farmer follows behind them, holding the plough. The ground is a slightly sloped hill, uneven and rocky with patches of grass, and both the horses and man appear tired. The background is made up of a clouded sky; a rolling landscape of hills, trees, and a cliff; and bundles of straw. The central image is surrounded by an intricate border, featuring a repeating pattern of ribbons, leaves, and fall produce, including squash and pumpkins. Two vertical white lines are visible, marking the boundaries where three sheets of two-foot-wide paper have been joined together to form the final picture.

-

ANDREA KORDA ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

To contextualize the print’s creation, Dr. Korda explains that the Art for Schools Association—a London-based organization dedicated to providing high-quality, inexpensive pictures to schools—commissioned the print. The Art for Schools Association was made up of Victorian leaders in art and education, and “The Plough” represents their first commission of a large-scale original print. Dr. Korda notes that the print offers insight into the contemporary British school curriculum: each item in the image (including horses, ploughs, soil, clouds, and produce) was included in the Education Department’s 1895 list of recommended topics for school lessons. However, despite its educational relevance, the print’s high cost and disappointing sales performance resulted in the Association taking a financial loss on this artistic venture.

A 1927 British Board of Education report on school pictures suggested that nineteenth-century schemes to provide pictures to schools, like that of the Art for Schools Association, failed due to a lack of clarity regarding the purpose of such pictures within the classroom. Were they intended to be used in direct instruction? Or were they intended as decoration? When it comes to “The Plough,” it is hard to imagine that the print offered much in the way of direct instruction since the plough itself is largely obscured. Given the makeup of the Art for Schools Association’s executive, which included aesthetes such as William Morris, George Frederic Watts, Arthur Mackmurdo, and Frederic Leighton, it seems more likely that the picture served as decoration and that the commission was motivated by the Art for Schools Association’s mandate, outlined in their circular of 1885, to inspire in children “a love for the beautiful … at an age when the mind is specially susceptible to the influence of habitable surroundings.”

However, Dr. Korda proposes an alternate reading of “The Plough.” She argues that we need not see prints like this one as either instructional or decorative; rather, they may offer an alternate pedagogical approach that embraces the Arts and Crafts principles valued by the Art for Schools Association. The Arts and Crafts ethos demanded that nothing be merely decorative or simply functional (or, in this case, instructional). Rather, decoration and instruction needed to be united so that every act of labour and learning could also be a work of art.

“The Plough” offers one such artful learning experience. Dr. Korda identifies a gap between what we see in the image and what we struggle to learn from it, which may make it seem less useful for direct instruction but also has the effect of opening up space for reflection and interpretation. This opening privileges the process of learning as more important than any one piece of correct information that could be derived from the print. Returning to the claims of the 1927 report regarding the confusion around school pictures, Dr. Korda notes that an emphasis on the learning process may have led to the confusion that future educators sought to eliminate. She argues, however, that the confusion resulting from a prolonged engagement with “The Plough” and other artworks has the potential to prompt curiosity, inquiry, and meaningful learning.