Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf"

Item

-

Title

-

Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf"

-

Description

-

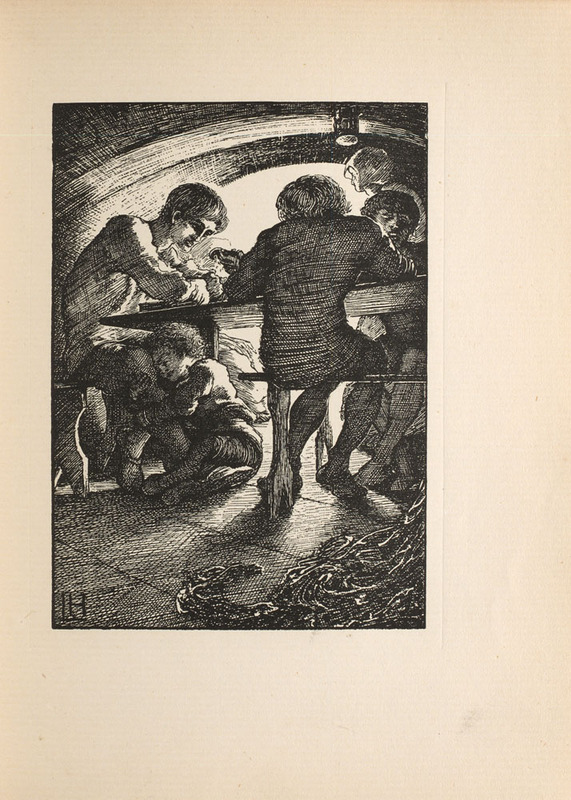

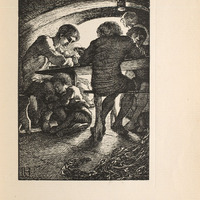

Clemence Housman’s "The Were-Wolf" is an illustrated novella published in 1896. Housman wrote the story and engraved the six illustrations, which were designed by her brother Laurence. The title page, printed in orange ink, acknowledges Clemence Housman as the author and Laurence Housman as the illustrator, as well as the novella’s publication date and its publishers in London and Chicago (John Lane and Way and Williams, respectively). However, as often happens in Victorian illustrated books, Clemence Housman’s role as the wood engraver remains unacknowledged. The engraved full-page illustration included here, “Rol’s Worship,” shows three young men working at a table; a small child hangs on to the legs of the man on the left. The background includes two women, partly obscured by the figures in the foreground. The various textures of wooden flooring, human skin, and fabric are represented by patterns of wood-engraved cross-hatched lines. Denser hatching suggests shadow on the ceiling and floor; white space and lighter patterns of lines show where backlighting brightens the scene. In the bottom left corner, Laurence Housman’s initials appear in block capitals. The complete, rectangular image is framed by white space but not centred on the page, leaving a greater amount of blank paper below and to the right of the illustration.

-

LORRAINE JANZEN KOOISTRA ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

Dr. Janzen Kooistra explains that wood engraving was Clemence Housman’s craft and shaped her lifelong career and artistic community. She argues that the title page and illustration demonstrate the significance of wood engraving for Housman: such engraving enabled her to support herself and disseminate her artisanal work.

Drawing our attention to the credits offered on the title page and subsequent images, Dr. Janzen Kooistra explains that the wood engraver’s labour goes uncredited not only on the title page but also on most of the illustrations. While Housman credits her brother Laurence’s labour as the illustrator by carving out his block initials on all six illustrations, Housman includes her own initials with more cursive lettering on only two of the six illustrations. Dr. Janzen Kooistra notes that this “self-effacement” on Housman’s part was both a personal choice and a product of Victorian print culture, which encouraged viewers to “look through the engraver’s cuts to see the artist’s composition.”

Dr. Janzen Kooistra redirects our attention to the handiwork of the engraver, pointing out that Housman’s labour is most evident in the negative spaces of the composition. These areas needed to be carved out from the surface of the wood in order to reveal the white spaces of the picture, which form the design. The network of lines on the surface of the woodblock are the ridges left untouched by the engraver’s tools, which, when printed in black ink on white paper, create the design out of positive and negative contrasts. Thus the most difficult labour goes into what the viewer does not see as work.

Despite Housman’s “self-effacement,” Dr. Janzen Kooistra notes that Housman’s engraving also included subtle, self-referential elements. The prominence of wood in the illustration “Rol’s Worship,” in the surfaces of the wood table and floor, and in the wood required to light the fire, reference Housman’s medium and craft. These references to Housman’s handiwork remind us that the picture seen by viewers, both today and when the novella was first published, is not what Housman saw as she engraved these images. The engraver sees individual cuts, inch by inch, while the viewer must visually unify the discontinuous lines to experience the image as a whole so that viewing the wood engraving becomes an interpretive act.