Mrs. Alexander's Mark

Item

-

Title

-

Mrs. Alexander's Mark

-

Description

-

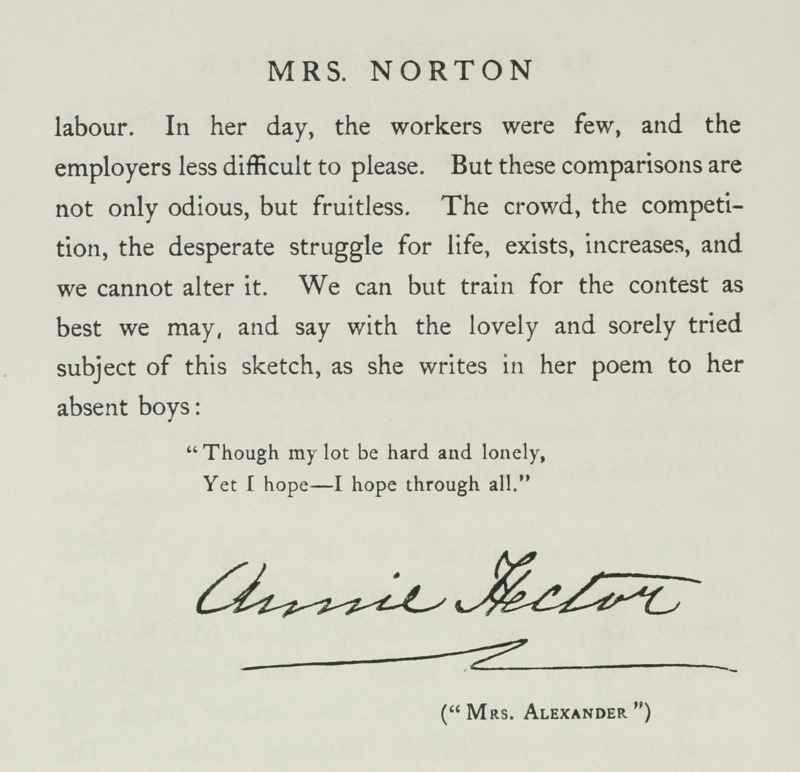

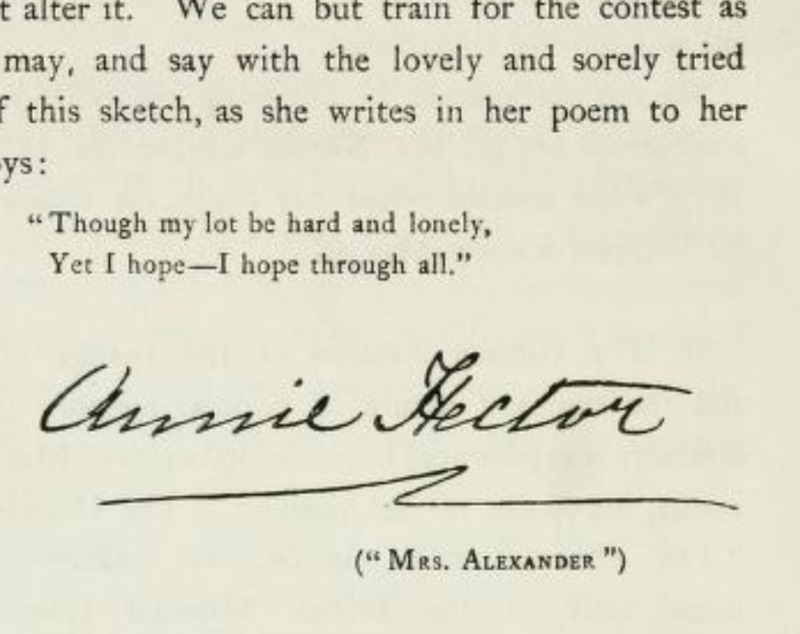

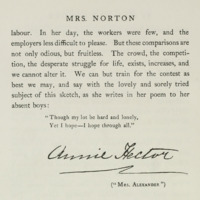

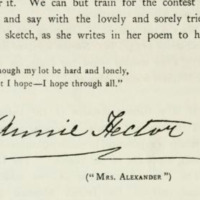

This page is from "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria’s Reign: A Book of Appreciations," published in London by Hurst and Blackett in 1897. It features standard black letter text on white paper. In addition to the body text, the page features three women’s names. First, “Mrs. Norton,” the subject of this chapter, runs across the top of the page. Second, the signature of “Annie Hector” appears directly under the body text at the centre of the page, underscored by a jagged flourish. Lastly, the name “Mrs. Alexander” appears inside both quotation marks and parentheses. Though the last name is in capital letters, its font is noticeably smaller than the two other names and somewhat smaller than the body text. The page number appears in parentheses at the bottom of the page.

The body text of the page reads:

labour. In her day, the workers were few, and the employers less difficult to please. But these comparisons are not only odious, but fruitless. The crowd, the competitions, the desperate struggle for life, exists, increases, and we cannot alter it. We can but train for the contest as best we may, and say with the lovely and sorely tried subject of this sketch, as she writes in her poem to her absent boys:

“Though my lot be hard and lonely,

Yet I hope – I hope through all.”

The copy of the book featured here is housed at the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library.

-

TALIA SCHAFFER ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

This page from "Women Novelists" provides insight into the lives of the women authors who wrote and were featured in this book. It also offers an opportunity to revisit second-wave feminist critical assumptions about Victorian women writers’ authorial names.

Mrs. Alexander, the author of this piece, and Mrs. Norton, its subject, both experienced difficult divorce proceedings, and both turned to writing as a source of income after leaving their husbands. On the surface, it seems as though both were compelled to publish under their married names, but Dr. Schaffer challenges this assumption. For one, Mrs. Alexander uses her husband’s given name “Alexander,” rather than his surname of Hector, and encases the name in quotations, as Dr. Schaffer notes, “mark[ing the] name as a fiction, an invention by a writer.” Second, she provides the signature “Annie Hector,” choosing to go by “Annie” rather than Anne, her legal name, a nod to the Irish origins of which she was proud.

These various signatures position Annie Hector between the historically available choices for nineteenth-century married women writers: either to take or to refuse their husbands' names. While second-wave feminists advocated for women to use their own names rather than their husbands’ names, Dr. Schaffer proposes that this page offers an opportunity for a more nuanced approach—namely, for the possibility that Annie Hector/Mrs. Alexander wanted her identity to encompass both of these names, simultaneously “record[ing and] danc[ing] away from her marriage.”

Dr. Schaffer also highlights the jagged underline beneath the signature “Annie Hector.” This line, Dr. Schaffer argues, is perhaps the best surviving remnant of Annie Hector’s identity—a line that, while both separating and connecting the two names, indicates “a life with its own twists and turns, with one catastrophic bump in the middle.”