Charlotte Brontё’s “Little Book”

Item

-

Title

-

Charlotte Brontё’s “Little Book”

-

Description

-

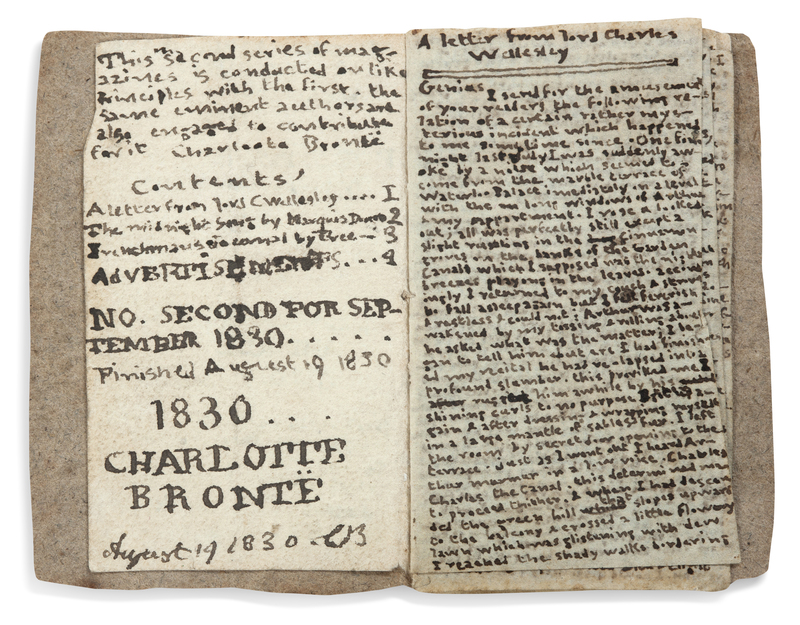

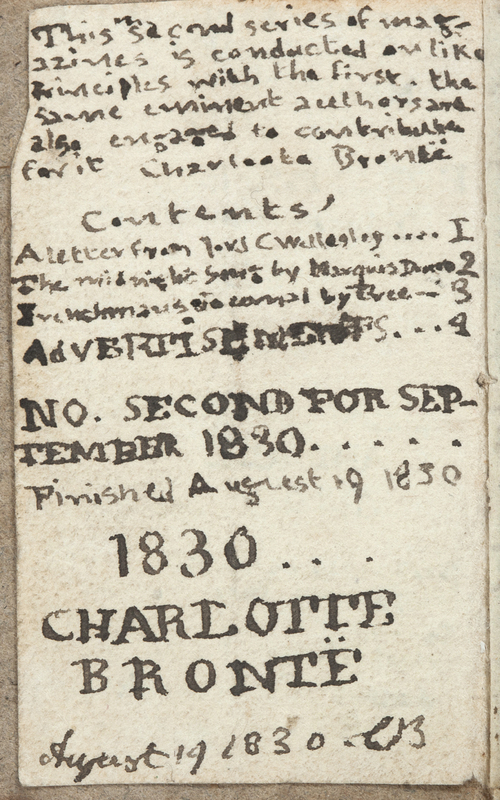

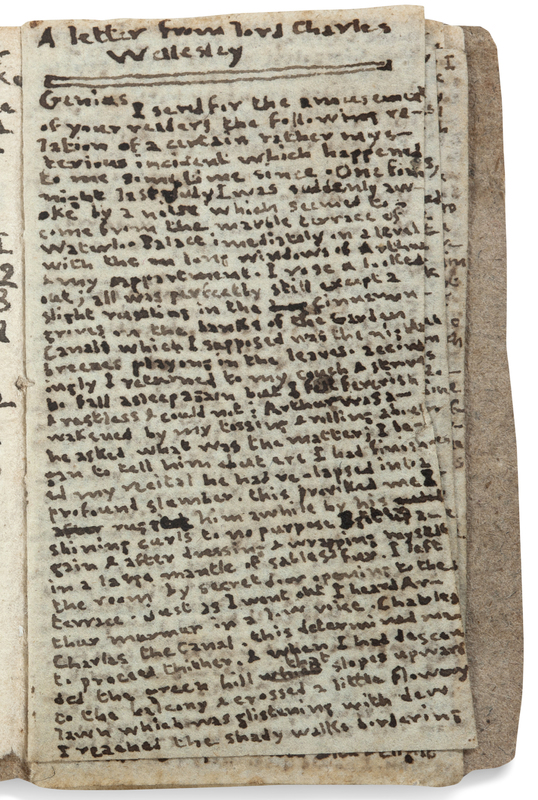

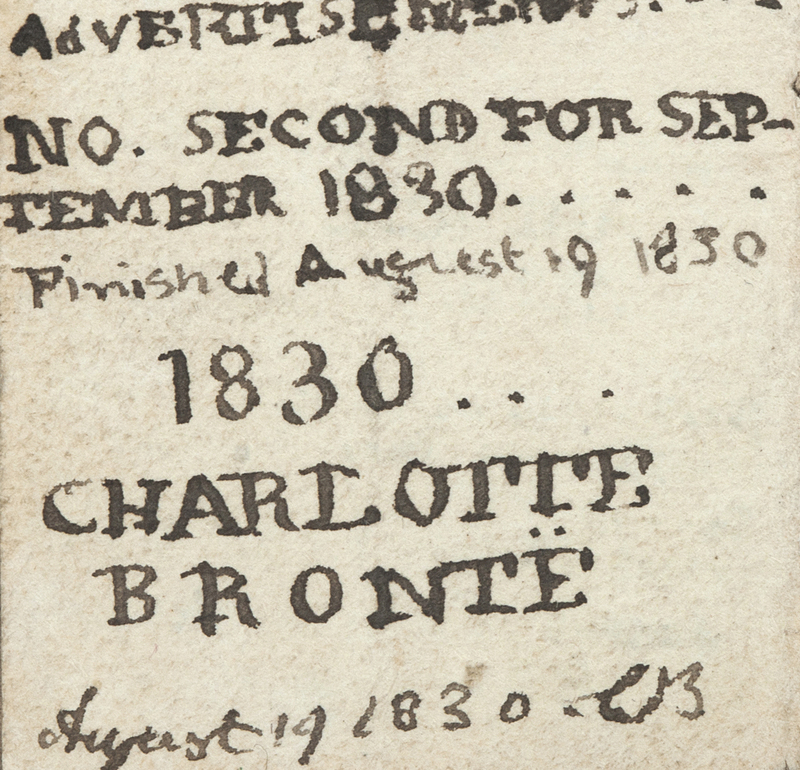

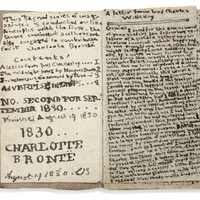

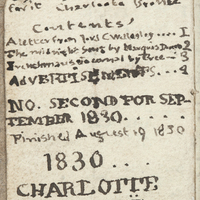

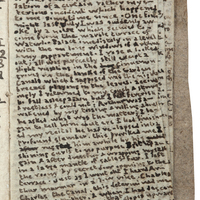

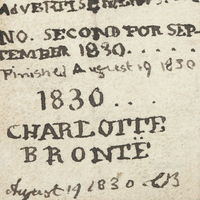

This “little book” by Charlotte Brontë contains an edition of "The Young Men’s Magazine," created in 1813 when Charlotte was just 14 years old. The size of a matchbox, the book features neat but cramped handwriting in black ink. The left-hand side of the left page lists the book’s contents with titles and corresponding page numbers. Below the contents, the year 1830 and the author’s name in all capital letters appear prominently across the bottom third of the page. The date of August 19 1830 runs across the bottom of the page followed by the initials CB. The right page has a title that corresponds to the first entry in the table of contents on the facing page and is filled with small, indeed barely legible, text.

-

DEBORAH WYNNE ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

As Deborah Wynne remarks, the tiny pages of this “little book,” which Charlotte sewed together herself, “charmingly suggest a miniature world of childhood.” Yet the book contains hidden stories beyond the ones written by Charlotte, its paper disclosing stories of Victorian textile production and recycling. The book is made from textile waste, perhaps a discarded sugar bag or a thrown-away advertisement. During the Victorian era, paper was very expensive to manufacture and subject to the paper tax, imposed on all paper until 1860. For this reason, all but the wealthy practised thrift by recycling paper. Dr. Wynne suggests that the recycled paper Charlotte used for her book came from textile waste and may have contained threads from a wealthy woman’s chemise mingled with the rags worn by a beggar.

Victorian children often scavenged for materials they could use for toys or for other creative purposes, and the Brontës were no exception. The Brontë siblings’ storytelling may seem far removed from the experiences of street-children in cities across Britain, but many nineteenth-century orphans and abandoned children made their living from collecting rags. These scavenged rags were sold to dealers who traded with owners of paper mills, where textile waste would be made into paper. Dr. Wynne explains how the labour of vulnerable children who collected rags is silently embedded in sheets of paper on which texts were written and printed prior to the 1870s, when paper was no longer manufactured from textile waste. Charlotte’s book thus potentially contains within it traces of other children’s lives.

It is likely that Charlotte was aware that the scraps of paper she salvaged for her “little book” came from rags. Dr. Wynne wonders if perhaps “she fantasized that her hero the Duke of Wellington’s discarded waistcoat had somehow played a part in its construction.” Certainly, the stories she and her siblings wrote as children focus on fantastic transformations and improbable happenings. Indeed, the industrial process of turning rags into paper was often described by commentators during the nineteenth century as “magical.”

Charlotte’s “little book” was purchased at auction in 2019 by the Brontë Parsonage Museum for 500,000 pounds sterling. If and when we get to see the book on display, we may wish to think about the paper on which the book is written. As Wynne points out, it is worth pausing to imagine the threads of old clothes from which it is made “and the lives of all those Victorian children who were involved in textile production and recycling.”