Anarchists on the Web

This exhibit will examine the history of anarchist debate surrounding the Internet, particularly in regards to the tension between the potential for free, truly anonymous public discourse (with all its pros and cons) the Internet poses, and the reality of its use as a tool for corporate, political, and military control. From these debates about the Internet, and the increasing technologization of society more broadly, many sub-groups of anarchists have emerged. Cypherpunks, who advocate for anonymity, have led privacy movements denouncing social media and promoting cryptocurrency, and Internet pirates have engaged the world in numerous conversations about intellectual property and copyright laws. On the other end of the spectrum, anarcho-primitivists, who are anti-technology and vie for a return to pre-Industrial Revolution society, call for the destruction of the Internet entirely. Comparing selections from zines found in the University of Victoria’s Special Collections archives with manifestos, articles, and forum debates online, this exhibit will introduce and explain some key considerations anarchists have found in trying to make sense of the Internet and the social, political, and economic changes it has brought to the world.

In the interest of accessibility, this site is meant to be read as one page. All external sources referenced in this exhibit can be found free online, and are hyperlinked within the text. For a full list of sources, please view the Acknowledgements section at the end.

Introduction

What is anarchy?

In everyday speech, “anarchy” usually means out of control, disorderly, or chaotic. As a political philosophy, however, anarchism is in opposition to an Archos, the Greek word for “master.” People who identify themselves as anarchists are usually sceptical of government institutions and their ways of controlling society. Their ideal society, modelled after the Greek word anarkhia, meaning “without a ruler,” is one without figures such as presidents, prime ministers, or kings, but also without the institutions that maintain their control, such as police forces, militaries, national religions, and centralised banks, among other things. While anarchists vary in their beliefs and ideals, all anarchists are interested in resisting centralised systems of control and hierarchy.

What is the Internet?

The Internet is a global system of computer networks, a network of networks. The Internet has its origins in the military. During the 1960s, the United States Department of Defense wanted to find a way to share messages and information from one computer to another without having to physically cart around the massive “drum memory” most computers used for storage. Drum memory cylinders weighed about ten pounds each, and only stored 10KB worth of data—that’s only about 10 pages of a text document!

Despite its origins as a military tool, the Internet is quite anarchist in its organisation. Any participant in the network can share information to anyone, and there is no hierarchical structure the network follows. Anarchists themselves have noted this design as proof of their philosophy working in practice:

“Most people, including and arguably especially most digital technologists, can intuitively understand the principles of anarchic coordination. There are myriad examples of modern technologies with names such as consensus algorithms, cluster orchestration, and distributed ledgers (like "blockchains") that are, when you actually stop to examine them, fundamentally anarchic approaches to solving complex problems in environments with various degrees of trust between participants.” (Tech Learning Collective)

On the other hand, many engineers, corporations, and governments saw the anarchic design of the Internet as a weak spot:

“[The Internet’s creators were] no longer in charge. Nobody really was. Those with dark intentions would soon find the Internet well suited to their goals, allowing fast, easy, inexpensive ways to reach anyone or anything on the network.” (Timberg)

These predictions ended up being correct. As early as the Internet’s first days, already there were tech specialists and hobbyists finding ways to exploit the weaknesses of various networks. This community began with a group of academic researchers and programmers at MIT, but gradually began to expand as computer technology became more accessible to the general public. They began to call themselves hackers, describing themselves as people who enjoy “exploring the details of programmable systems and how to stretch their capabilities, as opposed to most users, who prefer to learn only the minimum necessary” (“Hacker”).

Phreakers, hackers, and freedom fighters

By the 1980s, home computers were becoming more common, and an increasing number of businesses, governments, and corporations were using the Internet in their daily operations. While computer usage was still not widespread, those who were interested in the technology were now able to communicate with each other online through email and online bulletin boards. In the hacking community, a number of ezines began to pop up in the mid-80s, the most notable being Phrack, a portmanteau of phreak and hack. Whereas hackers were mostly interested in computer networks, phreakers were interested in telephone networks. The two often worked together, as in those days, Internet access was often connected to a landline telephone—hence the term “dial-up” Internet. Thus, hackers could use phreaking methods to find the telephone numbers for modems belonging to businesses, which was a popular way to break into “private” business networks. Phrack helped bring together phreakers and hackers, but it was also a publication with a political agenda. Most of the editors and contributors to the zine were anarchists, and many cited this ideology as one of the key influences behind their fascination with technology.

Perhaps the most famous article ever published in Phrack was “The Conscience of a Hacker,” later renamed “The Hacker Manifesto,” first published in November 1986. The article was written by a figure known as The Mentor shortly after his arrest, and seeks to outline the thought processes and motivations of hackers so that the general public might better understand them. The Mentor describes the hacking community as a group of freedom fighters which oppose the government, the military, and corporations, and one that values independent thought, intelligence, and curiosity over nationality, gender, race, or religion:

“This is our world now... the world of the electron and the switch, the beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying for what could be dirt-cheap if it wasn't run by profiteering gluttons, and you call us criminals. We explore... and you call us criminals. We seek after knowledge... and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color, without nationality, without religious bias... and you call us criminals. You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, cheat, and lie to us and try to make us believe it's for our own good, yet we're the criminals.

Yes, I am a criminal. My crime is that of curiosity. My crime is that of judging people by what they say and think, not what they look like. My crime is that of outsmarting you, something that you will never forgive me for.” (The Mentor)

This idea of the Internet as a place where everyone could be equal was very popular among anarchist hackers in the 80s and 90s. Outside of Phrack, one of the other major electronic publications connecting anarchists in the computer scene was the Cypherpunks Mailing List.

Cypherpunks are mainly interested in matters regarding surveillance and privacy, and advocate for the use of cryptography, or secure communication, to protect people from the prying eyes of governments, militaries, and corporations. Cryptography as a technique has been practised for thousands of years in various forms: Ancient Greek armies often wrote confidential information in code so it couldn’t be understood if intercepted by enemy forces, Nazi generals received and gave orders in a complex, ever-changing code that could only be deciphered using early computer technology in World War II, and modern credit cards use cryptographic smart chips to prevent fraud. Cypherpunks aimed to use these technologies to anonymize communication in a world where the Internet was making it increasingly easy for powerful entities to spy on everyday people. In addition, Cypherpunks wanted to apply this technology to economic exchanges. By applying cryptographic technology to currency, they could make transactions between parties impossible to track or trace. This was the beginning of cryptocurrency—once only an idea shared by a few Cypherpunks online, and now a reality.

Timothy C. May was one of the leading figures in the Cypherpunk movement, and a creator of the Cypherpunks Mailing List. In 1988, he published “The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto,” which outlined the ideology and goals of the movement:

“Computer technology is on the verge of providing the ability for individuals and groups to communicate and interact with each other in a totally anonymous manner… These developments will alter completely the nature of government regulation, the ability to tax and control economic interactions, the ability to keep information secret, and will even alter the nature of trust and reputation…

The State will of course try to slow or halt the spread of this technology, citing national security concerns, use of the technology by drug dealers and tax evaders, and fears of societal disintegration. Many of these concerns will be valid; crypto anarchy will allow national secrets to be trade freely and will allow illicit and stolen materials to be traded. An anonymous computerized market will even make possible abhorrent markets for assassinations and extortion. Various criminal and foreign elements will be active users of CryptoNet. But this will not halt the spread of crypto anarchy.” (May)

Both “The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” and “The Hacker Manifesto” share two main themes: the struggle between anarchists and state or corporate entities for control over the Internet, and the excuse of “cracking down on crime” used by these entities to justify potential oppressive, over-regulatory, and voyeuristic laws and technologies applied to the Internet by them. These themes will feature heavily throughout the three items this exhibit focuses on, and have been at the centre of anarchist’s discussions about the Internet for decades.

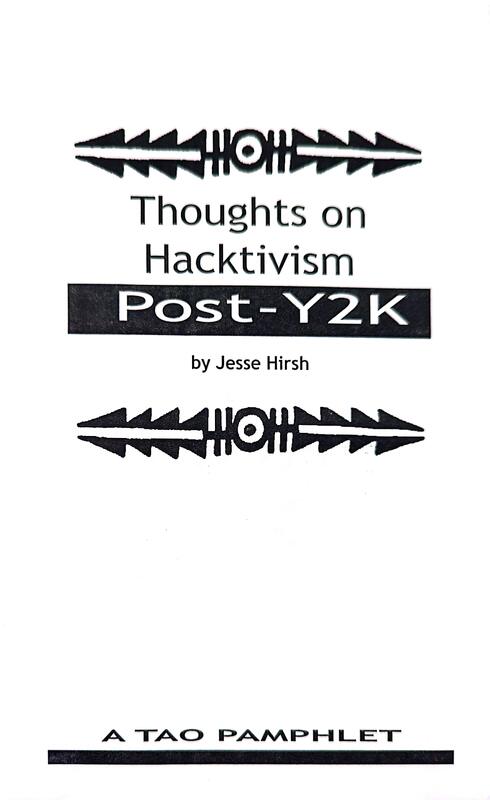

Thoughts on Hacktivism Post Y2K by Jesse Hirsh

This pamphlet was published by TAO (“The Anarchy Organization”) in Toronto, Canada, in January 2000. In it, author Jesse Hirsh argues that Y2K as a spectacle event was a symptom of the sense of mystical confusion and awe much of the public feels when interacting with the Internet. Because the average person doesn’t understand the inner workings of the networks and technologies they use, the Internet exists to them as a product they can interact with but not understand. Hirsh argues this is intentionally done by corporations to alienate users and retain their power over the Internet as a social tool. Hackers complicate this corporate power. Hacks both destabilise public trust in corporations' ability to preserve their data online, and increase public interest in the inner workings of networks and computers. Hackers have thus become key figures in imagining the Internet as a site where corporate and government control is exerted, but also as a site for social change.

The cover art, as well as a transcription of the first half of the pamphlet, is included below.

"It would appear that the most important, if not essential aspect of surviving in this ‘post-Y2K’ society has become the task of “Understanding Reality”. That is to say, our society has reached such a high level of media saturation, that reality is not so much an objective experience, but more a subjective construct facilitated by a sprawling economy that combines telecommunications, computers, marketing, and entertainment, to generate a facility that more and more permits the customization of reality, when and where possible. Power in this system manifests as the ability to control, contain, maintain, and escape one’s constructed reality. As with most political systems, power is centralized and continuously accumulated into the hands of the few, while the appearance of distributed wealth is enabled by the reality of distributed computing and communications. For every remote control there is the illusion of change, even when we all know that everything is the same, regardless of the channel.

For most people however, reality bites, and it bites hard. The values that the society presents as the bonds of its existence, include accumulative and possessive individualism, often at the expense of the society (and social fabric) itself. We are told that happiness is in success, that success is in power, and that power comes with money, so we need to get mo’ money and mo’ money, by any means necessary.

Hacking Reality is the means by which we can reclaim our communities and struggle towards an equitable and democratic society. Within this technological system that surrounds us, the Hacker struggles to become human. We are all born animals, but via socialization with each other, and our environments, we become the human being that we’re instinctively driven to become. What sets the Hacker apart from other identities in our society, is the considerable effort and ongoing change that the Hacker undergoes to understand, and furthermore, transform, the environment in which they reside. Contrast this with the average Consumer, who has discarded their humanity, in favour of a much more reliable and secure corporate identity, that guides them through the trends and fads of their culture. The Consumer does not understand or attempt to transform their environment; rather they accept it as it is, conforming to whatever changes the system presents.

What these two identities hold in common is an existence within a dynamic and ever changing system. For as we all see and hear: the only constant in our world, is change itself. What sets the Hacker apart, is their possession of social power, which is largely derived from an understanding of their environment (aka: reality). For within this technological society, there are always inherent mechanisms of power built into the logic and operations of its systems. Colloquially this is referred to as “God Status”, and most frequently manifests as a systems’ root account. While these powers generally exist (and were intended) for administrative purposes (and control) they can also have countless secondary and tertiary applications, especially when it comes to unintended applications or possessions of said power.

As a culture, and as a set of social networks, Hackers have been uniquely successful in both understanding the presence and role of this power (within the system) as well as being able to both subvert and broaden the access to said positions and mechanisms of power. Out of this particular ability, if not potential social role, has emerged the concept of Hacktivism, which while widely used (by the mass media) really does not have a consensual definition that is accepted by all actors in the culture. For the purpose of this discussion however, let us define Hacktivism as: Social Activism augmented by an advanced literacy of communications environments. For one of the largest tensions that is underlying many of the conflicts in our technological society is the contrast between open source shared organizing, and closed proprietary development. In the realm of Hacktivism, this is the difference between the military-centric strike teams, and the social-centric hackers (and groups) who freely give out source code and intelligence that they gather.

Most of our technology, indeed, most of our communication environments, were originally, and for the most part still are, the domain of the military. This is not to say that economic and civil activities cannot simultaneously co-exist, but it does mean that any telephone and computer is within reach of the eyes ears and guns of the military and state intelligence establishments. This only serves to emphasize and highlight the need for a broader sphere of Critical Collaborative Free Open Source Distributed Development.

Essentially we are all squatters on the largest military base ever created, and it is the role of Hacktivists to help the residents of the squat (o/k/a society) understand what it is they can do with the facilities (Internet) as part of a greater struggle to be human beings living in a social world." (Hirsh)

Hirsh pits the Hacker against the Consumer as two seperate roles in capitalist society. Whereas the Hacker fights for freedom and actively pushes back against corporate and state control, the Consumer is content to live by the rules and regulations these powers enact on the population. Computer literacy is thus an important aspect of fighting back against the powers that be in the 21st century.

Perhaps more importantly, however, is Hirsh's focus on copyright, propietary vs. open source software, and intellectual ownership. In the past, copyright largely existed for physical inventions, in the form of patents. But the rise of white collar and intellectual or creative work as industries in the past century, and more importantly, the rise of advertising, corporate branding, and merchandising, has shifted the idea of copyright from patents to more nebulous legal guidelines. The Internet has further complicated copyright. Piracy is exceptionally easy online, and due to the uncentralized, anarchistic design of the Internet, as discussed earlier, it is difficult for law enforcement agencies and corporations to catch pirates who share copyrighted materials online. This, Hirsh argues, is another area where the Hacker can resist government and corporate control.

First, the anarchistic design of the Internet allows the Hacker to post intelligence unearthed by their exploits online in a manner that is virtually impossible for governments and corporations to stop, control, or keep from spreading. WikiLeaks, for example, has posted more than ten million documents stolen by hackers from entities such as the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the Church of Scientology, the British National Party, and the U.S. Department of Defense. So far in 2023, the year this exhibit was created, hackers have posted the U.S. No Fly List on BreachForums, a popular hacking forum. Authorities struggled for days to have the post taken down, and by the time they succeeded, the information had spread so far and wide it could no longer be contained.

Secondly, the ability to develop and distribute open source software has undermined corporate control over technology. Alternative operating systems like Linux have stolen from the monopoly of Windows, and free, open source alternatives to subscription services like Adobe Suite and Microsoft Suite have become increasingly accessible and popular over the years. Cracked versions of propietary software are also distributed on online piracy sites, further taking away from the control large tech corporations have over the Internet.

In this way, the Hacker has become a modern-day Robin Hood, stealing classified information, leaking documents, and making copyrighted, expensive software and entertainment free for the masses. When the Hacker helps the Consumer view the Internet as a tool of resistance rather than consumption and complacency, the Internet can exist as a tool for social change.

from knapping to crapping: running riot through the supermarket of skills!

This resource list, published in Do or Die: Voices from the Ecological Resistance vol. #8 in 2005, serves as a catalogue pointing to informational zines on a variety of topics. Its section on hacktivism includes several resources about the history and practical application of hacking techniques, mostly related to creating viruses, finding ways to steal free Internet access or phone calls, and protecting personal information from scammers and governments alike.

Much like Hirsh's article, "from knapping to crapping" advocates for education about the inner workings of computers and the Internet as a way of resisting corporate and government control. Much of the tutorials pointed to in "from knapping to crapping" focus on how to obtain products and services for free, either through piracy or through more straightforward thievery. Many anarchists online have pointed to the possibilities for destablizing private property that the Internet presents as part of its revolutionary potential. For example, Humanaesfera writes in 2018:

"One of the most basic features of computing is the exact copy of information at almost zero cost. Even before the Internet, ever since the emergence of digital computers (especially PCs), there was already an extensive network of users around the world who transmitted free or pirated programs, files, books, images, codes, etc., on magnetic tapes or diskettes. The world wide web is nothing other than this data-copying network become automatic and instantaneous via telecommunication repeater stations, which span the entire globe with fiber optics, cables, and radio frequencies.

The copying and dissemination of information thus becomes a universal community where data can be made available by anyone for everyone and vice versa. Moreover, this occurs almost in real time. It can include everything from live reporting on events to reserves of knowledge, both practical ( how to fix things or even construct them) and theoretical. A multiplicity of reports equally accessible to all who sought them, combined with a variety of views on any given topic, allowed individuals to form fairly objective ideas about events and topics that affected their life.

Digital transmissions of information fundamentally ignore scarcity, which forms the basis of private property, because such transmissions are themselves already copies. Not by chance, this word “copy” originated from the Latin copia — as in copiousness, meaning “abundance, ample supply, profusion, plenty” (from co- “together, with, in common” + ops [genitive opis] “power, wealth, ability, resources”).

Yet this is absolutely intolerable in a society founded upon constant buying and selling, which requires everyone to strive tirelessly for the continued imposition of scarcity — i.e., privation — as the absolute condition for survival within generalized competition." (Humanaesfera)

Moreover, one of the most suggested forms of resistance offered to those looking to join the ranks of Internet anarchists is committing piracy. The article "How To Start a Hackbloc," published by Hack This Zine! vol. 4 in 2006, suggests the following as ways to resist corporate control online:

- Hold workshops on online security culture: showing people how to use and install tor/privoxy (secure proxy through onion routing), using SSL on IRC, off the record (for secure AIM chats), pgp/gpg, how to clear your system of temporary files, internet caches, "deleted" files, etc

- Explore alternatives to copyrights / anti-copyright activism: have a 'pirate file share fest', set up file servers on the network, promoting creative commons/copyleft /anti-copyright media and projects

- Have a "linux fest" and play with various distros and livecds, encouraging people to bring their machines + install or dual boot linux. (Hack This Zine!)

Linux is another tool of resistance often talked about by anarchists online. As I have previously mentioned, Linux is an operating system often touted as an alternative to Microsoft Windows. It has been heavily criticized by tech companies for "encouraging piracy" and other acts of Internet crime, as there are no anti-piracy measures built into the software (unlike Windows Defender, which flags pirated files and can even prevent torrenting programs from running).

Linux for Punks

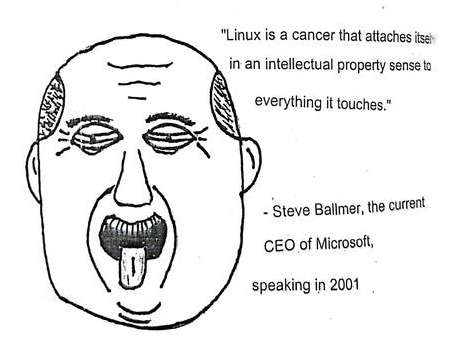

This informational zine, self-published by the author in 2009, guides readers through the process of setting up Linux, an open-source, free operating system meant to rival mainstream corporate operating systems such as Microsoft Windows or Apple macOS. The author includes satirical drawings of Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, who railed against Linux for its connections to the anti-copyright and piracy movements, juxtaposed with quotes from Linux’s creators about the importance of not relying on corporate, privately-owned software.

Linux has been around since the mid-1990s, and while it is not popular with the general population, it is highly popular among hackers, Cypherpunks and those interested in privacy, cyber-criminals, whistleblowers, and DIYers. There are two main reasons for Linux's relatively unpopularity: one, it requires a small amount of programming knowledge to install and use, which most of the population doesn't possess; and two, it does not come pre-installed on most computers. Manufacturers like Dell and Acer have agreements with Microsoft to sell their computers with Windows as the default operating system. All of Apple's computers use MacOS, and usually cannot run programs intended for Windows. Selling computers with these two standard operating systems pre-installed allows tech corporations to maintain a level of control over how users use their devices, and de-incentivizes the use of free, open source, community generated operating systems like Linux.

However, whether the open source model is truly revolutionary or a good use of the potential for social change the Internet holds has been doubted by some:

"The Linux system is produced collectively by many people from different parts of the world, collaborating together out of their own choice in order to produce a product for free. The free association of producers, production for use not exchange, international community: is this communism? Well maybe, but if it is, then communism is no big deal. Freeware may well reduce the revenue of commercial software houses a small amount. Certainly the communist impulse of those that produce for free is exemplary and should be recognised as such. But there seems little in this activity that truly threatens the status quo." (Antagonism)

Nonetheless, Linux's enduring connections to the anti-copyright movement have made it popular among Internet anarchists. As the comic featured in "Linux for Punks" to the right indicates, Steve Ballmer, the CEO of Microsoft at the time of the zine's creation, famously stated that "Linux is a cancer that attaches itself in an intellectual property sense to everything it touches."

As Rickard Falkvinge wrote in his article "I Am a Pirate," published in Hack This Zine! in 2006, it may be true that the financial losses corporations suffer from piracy isn't the real danger the crime poses. After all, to pirate software or media isn't necessarily to steal it—no physical product with attached production costs is taken, but rather, the publisher loses the potential of a sale. Instead, Falkvinge argues, the outrage generated surrounding piracy is more about monopoly and control:

"Downloading is the old mass media model where there is a central point of control, a point with a 'responsible publisher', somebody who can be brought to court, forced to pay and so on. A central point of control from where everybody can download knowledge and culture, a central point that can grant rights and take them away as needed and as wanted.

Culture and knowledge monopoly. Control.

Filesharing involves simultaneous uploading and downloading by every connected person. There is no central point of control at all; instead we have a situation where the culture and the information flow organically between millions of different people." (Falkvinge)

As I described at the beginning of this exhibit, the organization of the Internet follows an anarchist structure. Filesharing, torrenting, and piracy further exploits this anarchic design. The lack of centralized control within the Internet has long been a source of anxiety for governments and corporations alike, but has been exalted and joyfully manipulated by anarchists online. As these three items have shown, the struggle between the state and the people to claim the Internet as their own has been ongoing for decades. However, anarchists argue, if the population were to increase their skepticism and computer literacy, and understand how to use the Internet for means other than consumption, it might tip the needle of control away from governments and corporations in a more permanent way.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded through the Peter and Ana Lowens University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections Student Fellowship. I am very thankful to Peter and Ana Lowens for their generous support in making this exhibit possible. I would also like to thank Heather Dean, Lisa Goddard, and Jentery Sayers for their guidance in creating this project.

This project was produced on the unceded traditional territory of the lək̓ʷəŋən peoples, and the Songhees, Esquimalt, and W̱SÁNEĆ First Nations.

This exhibit was made by Asia :)

Sources

Note: none of these sources are "academic" in nature, and most are missing dates, authors, and other key identifiers. As such, these citations are likely incomplete.

Antagonism. “Technoskeptic.” The Anarchist Library, 20 Feb. 2011, theanarchistlibrary.org/library/antagonism-technoskeptic.

Falkvinge, Rick. “I Am A Pirate.” TED Talk, www.ted.com/talks/rick_falkvinge_i_am_a_pirate?language=en. Accessed 24 May 2023.

“Hack This Zine! 04.” The Anarchist Library, 2006, theanarchistlibrary.org/library/hackthissite-org-hack-this-zine-04.

“Hacker.” Jargon Files, www.catb.org/jargon/html/H/hacker.html. Accessed 20 May 2023.

Humanaesfera. “A Social History of the Internet.” The Anarchist Library, 2018, theanarchistlibrary.org/library/humanaesfera-a-social-history-of-the-internet#toc4.

“The Internet Was Always Anarchist, so Anarchists Must Learn to Become Responsible for Operating It.” Tech Learning Collective, 8 Oct. 2020, techlearningcollective.com/2020/10/08/the-internet-was-always-anarchist-so-anarchists-must-learn-to-become-responsible-for-operating-it.html.

May, Timothy C. “The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto.” The Anarchist Library, 1988, theanarchistlibrary.org/library/timothy-c-may-crypto-anarchist-manifesto.

The Mentor. “The Conscience of a Hacker.” ., 8 Jan. 1986, www.phrack.org/issues/7/3.html.

Timberg, Craig. “The Real Story of How the Internet Became so Vulnerable.” The Washington Post, 30 May 2015, www.washingtonpost.com/sf/business/2015/05/30/net-of-insecurity-part-1/.